Beyond any border something new begins. Not many men have crossed as many borders and boundaries, cultural, cartographical, anthropological as well as zoological, as Robert Jacob Gordon did. He was a mind-broadening and pioneering person who opened up, quite literally, new horizons in an ever changing world. This introduction to Robert Jacob Gordon was written in Dutch on 25 October, in commemoration of the anniversary of his death in 1795.

A mind-broadening explorer

Robert Jacob Gordon (1743-1795) was a truly remarkable man living in an equally remarkable and turbulent time in history, when borders were pushed back, boundaries overstepped and drawn again. Literally and figuratively. An infinitely intriguing and enchanting man. Born as a Dutchman with Scottish roots, he became a well known person during his lifetime, in different social and political circles, and in all walks of life. Among professors, scientists, military and travelers, and among European nobility and royal families. Gordon was a Scots Brigade officer in service of the Dutch Republic, and later commander and ‘diplomat’ of the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC, the Dutch East India Company). He was an explorer, cartographer, anthropologist, zoologist and botanist, all in one. A colourful adventurer.

Gordon crossed many boundaries and went on several long journeys through the largely unspoiled interior of 18th century Southern Africa. Here he explored the borders as they were drawn up, crossed these, and set out into territories as yet untouched and unnamed by Europeans. Wherever he went Gordon looked for new species of plants and animals. In time he would rename the Grote Grensrivier in Oranjerivier, in honour of his hero, the Prince of Orange, Willem V.

Cherishing the great unknown

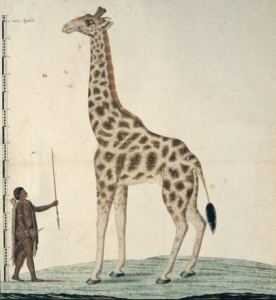

The large, often hardly known animals, were shot for study and examination: measured, dissected, and meticulously described and drawn. Among these ‘new’ animals were the rhinoceros, hippopotamus and – Gordon’s personal favourite – his ‘Camel-horses’, known to us as giraffes. With the giraffes Gordon made an immediate impression in Europe. Everything he saw and met on his expeditions was recorded, collected and where possible transported back to the Dutch Republic by ship and delivered to professor Jean Nicolas Sébastien Allamand (1713-1787) in Leiden, and Aarnout Vosmaer (1720-1799), director of the Prince’s zoological garden in Den Haag, and head of the Museum for Natural History.

Sincerely interested Robert Gordon searched for the many different people living in Southern Africa. He became friends with tribal ‘captains’ he met on his travels. He studied and shared in their way of life in the ‘kraals’, the native settlements. Gordon made descriptions of the major native people, known as Hottentots (Khoikhoi), Kaffirs (Xhosa) and Bushmen (San). He was touched by their lives, their poverty, the advancing colonization, and the subsequent conflicts with the white ‘trekboeren’ or boers, that were already emerging at this time. Gordon’s sympathy clearly was with the native people.

Experiencing and describing

With his expeditions and descriptions of the landscape, people, flora and fauna, Robert Jacob Gordon shifted the boundaries of ‘knowledge’. Many scientific disciplines are indebted to the wealth of information Gordon discovered, described, and depicted. He has left an impressive collection of journals, maps, drawings and paintings. The extraordinary ‘Atlas Gordon’ is currently to be found in the collection of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (just have a look online). A splendid summary in Dutch of Gordon’s travels is given by Luc Panhuysen in his book, written for the Rijksmuseum in 2010, ‘Een Nederlander in de Wildernis, De ontdekkingsreizen van Robert Jacob Gordon (1743-1795) in Zuid-Afrika’.

Everything that makes history fun comes together in the colourful person of Robert Jacob Gordon. History encompasses all, everything becomes history. Not only Gordon’s life, his travels and discoveries are exceptionally gripping and interesting, so is the time and world he lived in. It was an age of – several forms of – Enlightenment, a time where discoveries, perceptions and scientific developments evolved enormously. Physical, cultural and political boundaries were crossed, questioned and set down. In this period of time constitutional boundaries were drawn up again and redefined with the American War of Independence, the French Revolution, and the continuous changing balance of power and alliances between countries and empires.

The explorer explored

In the midst of all this walks a ‘man of his time’, an ‘enlightened person’. Genuinely interested and full of wonder. Robert Jacob Gordon sets about to explore, to experience and to record. He came, he saw and he described. He put his surprise and discoveries on the map. There is, however, still much to discover about the man himself too. Research into Robert Jacob Gordon is in itself a fascinating exploring expedition.

Robert Jacob Gordon was born on 29 September 1743 in the garrison town Doesburg, where he was raised among families of soldiers and officers, and in turn recruited for one of the Scots Brigades of the Dutch Republic himself. He was admitted to the University of Harderwijk, stayed in the famous university city of Leiden, and suddenly found himself – or better: we find him – back in southern Africa in 1772. Traveling, collecting and amazed at everything he encounters and discovers, and so are we. When he arrives back in Leiden in 1774, there is only one thing on his mind: to get back to the ‘wilderness’ as soon as possible.

Where did his passion and interests come from? Was it as a child, among the officers and soldiers in Doesburg – they were ‘travelers’ too, after all? Or was it at university in Harderwijk, or in the metropolis and city of science, Leiden? How did he get to southern Africa in the first place, did he choose consciously, or was it pure by chance because a ship to Cape Town had a place available? Could it just as easily have been the East or West Indies? And, as intriguing, how did an officer in the Scots Brigade get the possibility, time and money, to ‘just’ leave and travel for a year and a half. Fascinating questions for which we do not have direct answers available at the moment. Great opportunities for further research though. A new voyage of discovery.

At home in the wilderness

In 1777 Gordon was given his chance, and he takes it with both hands. Thanks to influential friends in Leiden he embarks in service of the VOC for The Cape. On his way to new expeditions and new discoveries. A genuine man of his time, hopelessly ‘enlightened’, deeply in love with the unknown, fascinated by science and knowledge. An open mind and his eyes open for the ‘new’ world. All things have to be identified and put on the map. Robert Jacob Gordon the artist, painter and writer, adventurer and man of the world. From far and wide dignitaries, scholars and naturalists came to visit Gordon, eager for the stories and extensive collection in his house-museum.

At the same time he was anything but a man of his time. At any rate, he lost his grip on time and developments. Balances of power had shifted as a result of the various wars and revolutions in America and Europe. Gordon was, and felt more at home in the so-called wilderness of his travels and in the kraals that were threatened by white men. The lion’s den of the Cape, with its political and military games, obviously did not appeal to him. The administrative life where he, as VOC commander, came into conflict with the governor of the Cape Colony frequently, was the real wilderness for Gordon.

Striking the flag

Illustrative for his incomprehension, naïveté perhaps, is his unfortunate death. In 1793 the French declared war to the Dutch Republic and ‘tyrant’ Willem V. On 18 January 1795 Willem V took refuge in England at Kew Palace. Here he wrote the so-called Kew Letters, a circular note addressed to the governors of the various territories overseas. In the letters he called upon the addressees to co-operate with the English and consider the British naval forces as allies. Meanwhile the Patriots in the Republic had proclaimed the ‘Batavian Republic’ and abolished the office of stadtholder.

The moment a British fleet arrived at the Cape, in possession of the letter, Robert Jacob Gordon and the other administrators in the Cape Province did not yet know the Republic had a new government. The English however did. With help of Gordon the English were able to take the Cape, and instead of the Prince’s Flag the Union Jack was flown. Gordon thought he had acted dutifully and in commission of the Prince of Orange but had literally been deceived. Despised and called a traitor by his own troops, he became an outcast in the Cape Colony.

Present and future

On 25 October it was 221 years to the day that Robert Jacob Gordon shot himself in the garden of his Cape Town residence ‘Schoonder Sigt’, just over a month after the English hoisted their flag. He was a remarkable man in a remarkable world and worthy of remembrance and (re)discovery.

In a few months time, on 17 February 2017, a new exhibition starts at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam: ‘Good Hope? South Africa – The Netherlands‘. In it Robert Jacob Gordon will feature prominently, together with the landscapes, people, plants and animals he recorded in illustrations and texts. Let’s experience his adventures and amaze ourselves.

Nederlands

Nederlands